Keywords:

Urban imaginaries, Right to the city, Activism, Peer-production, City co-production, Civic engagement, Political participation

By Carlos Estrada-Grajales, Marcus Foth, Peta Mitchell

Introduction

2018 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Henri Lefebvre’s (1996) concept of le droit à la ville, or the ‘Right to the City.’ Lefebvre coined the phrase in 1967, but the book that bore the concept as its title was not published until the following year—a year that, in France, saw massive social upheaval and widespread protests, strikes, and occupations of public and private spaces and institutions. Half a century later, Lefebvre’s call for a shift in the ways citizens engage in urban governance is experiencing a resurgence all over the globe. In the last decade, critical urban theorists (Brenner, Marcuse, & Mayer, 2012; Harvey, 2012), and a spate of citizen movements challenging the status quo in city governance, have demonstrated the renewed relevance of the concept. Social movements including the Tunisian Revolution (Zemni, 2017), the Movimento dos Sem Teto da Bahia – MSTB – (Belda-Miquel, Peris Blanes, & Frediani, 2016), and Indignados in Spain (Corsín Jiménez & Estalella, 2013; Postill, 2014), are based on the right of citizens to reshape the city according to their need and desires.

Despite the significance of ‘Right to the City,’ both as a concept and as a social movement, scholarly literature on urban studies and social movements has focused mostly on understanding both the roles of private corporations and governments as regulators of social and economic activities in the city, and the justifications for their interventions (Fujita, 2013; James, Thompson-Fawcett, & Hansen, 2015; Weaver, 2016). Approaches from critical urban theorists (Marcuse, 2012; Mayer, 2012) have emphasised the urgency of investigating the specificity of citizen-based endeavours, such as ‘Right to the City’ and others claiming citizen co-ownership, for understanding how these organisations contest top-down urban power structures and governance-beyond-the-state practices (Swyngedouw, 2005), and generate ‘participatory urbanism’ (Foth, Brynskov, & Ojala, 2015; Jacobs, 1969) and ‘urban policies of the inhabitant’ (Purcell, 2002). We will unpack these themes further below (see section 2.1).

The underlying significance of understanding citizen responses to the contemporary urban crisis relies on the shifting role of citizens from passive residents to city co-creators. To investigate this shifting role in the context of Right-to-the-City-inspired urban activism, this paper focuses on a local organisation, namely Right to the City – Brisbane, that actively practises different forms of peer-production of the city by activating strategies for spatial appropriation, innovative protest, political participation, and citizen empowerment. Since its formation in 2015, Right to the City – Brisbane has consolidated an agenda against gentrification, the shortage of affordable housing, private development and marginalisation of citizens from decision-making mechanisms in Brisbane, Australia (“Right to the City Brisbane,” n.d.). In this paper, we present an ethnographic account of the organisation’s principles, actions and agendas. We use Harvey’s (“David Harvey: The Right to the City,” September-October 2008, p. 1) questions about “what kind of city […] what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire” to examine how Right to the City – Brisbane conducts local activism and engages citizens in the peer-production of Brisbane.

The paper first outlines a threefold literature discussion about how citizens shift their roles from passive residents to peer-producers of the city in the context of urban crises, the Right to the City concept, and the production of imaginaries (Cinar & Bender, 2007; Silva, 2012; Westwood, 1997) as narrative mechanisms in citizen-centred urbanism. Second, we outline our methodological approach describing our epistemological approach and expanding on the research method we use for collecting and analysing the data. Third, we present and discuss our findings focusing in three sections related with how Right to the City – Brisbane engages, and crafts the city. Finally, we present our research conclusions.

Prior work

In the following, we will critically review and discuss prior work relevant to our study. We will do so in three sections: (a) New means for citizen peer-production of cities; (b) Right to the city: citizen responses to the crisis, and; (c) Imagining a citizen-led urbanism: city-production in future tense.

New means for citizen peer-production of cities

Cities are more than built spaces: they are historical, social and political products. When applying Lefebvre’s trialectic lens (Lefebvre, 1991; Soja, 1998) to understand how cities are produced, one can argue that specific cities are the result of how certain individuals, organisations and authorities conceive the urban space, how the urban space becomes a system of signs conditioning residents perceptions, and how such conceived and perceived space is experienced and practised daily by citizens in general (Lefebvre, 1991; Stewart, 1995).

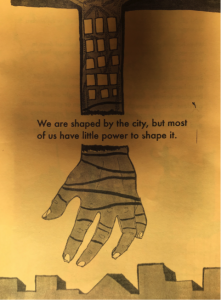

The processes that socially produce cities are embedded in a constant power struggle among numerous agents with different levels of leverage (Harvey, 2012; Jacobs, 1969). The ongoing influence of capitalism in political decision-making (Harvey, 2003a; Weaver, 2016) is being expressed by globalised neoliberal practices in urban governance under the umbrella of ‘urban crisis’ (Weaver, 2016). An array of social and political effects, including the rise the levels of inequality and unequal wealth distribution (Forum, n.d.; “Global Economic Inequality,” n.d.), the increasing of disenfranchisement in lay citizens (Purcell, 2002), and the direct influence of ‘private economic actors’ as an example of governance-beyond-the-state (Swyngedouw, 2005, p. 1992), have been utilised by local governments to justify political and economic interventions in cities (Weaver, 2016), and decrease democratic mechanisms for citizen participation in the process of shaping cities (Aarsæther, Nyseth, & Bjørnå, 2011; Castells, 1986; Falk, 2000; James et al., 2015). Frictions between impositive planning authorities and ‘awakening’ citizens, already outlined by Jacobs (1969) in american cities during the social uprisings in the 1960’s, delineated the context in which citizen-led movements, particularly Right to the City, have emerged in recent years (“Right to the City,” n.d., “Right to the City Brisbane,” n.d.). Corsin and Estalella (2013), for instance, report how, by considering the tension between vecinos (neighbours), their socio-political interactions, and the space they socially produce in the context of Madrid’s Popular Assembly protests in 2011, ethnographic reasoning may address the specificity of citizen-based co-production of the city.

Despite those threats, urban residents are finding innovative ways to co-produce cities. There are examples of how urban residents use different technologies to engage in civic matters (Foth, Schroeter, & Anastasiu, 2011; Klaebe & Foth, 2007; Klaebe, Foth, Burgess, & Bilandzic, 2007). Citizen appropriation of digital tools, as well as the reorientation of strategic organisation schemes in response to the effect of global urban crises, have fueled the emergence of citizen attempts to claim their rights to the city and being more informed agents in the process of co-producing it.

Digital technologies and new forms of civic organisation reshape the forms in which urban residents understand and interact with their cities (Brynskov et al., 2014; Schroeter, 2012), and by extension redefine the power struggles that underlie urban governance (Houghton, 2014). By using tech-based tools (Foth et al., 2011) and face to face mechanisms (Mayer, 2012), citizens, both individually (Cranshaw, Schwartz, Hong, & Sadeh, 2012) or as part of activist movements (Postill, 2014; Rekow, 2015) transform their role from passive residents to city co-producers (Foth et al., 2015). The shift in the way urban governance is challenged by bottom-up approaches (Iveson, 2013), enables citizens to pursue common goals in a decentralised form, to aggregate a multitude of civic motivations, and to transform the purposes of the common good and public service. Citizens, then, appropriate, re-imagine and execute forms of civic intelligence (Schuler, De Cindio, & De Liddo, 2015) and city peer-production (Benkler, 2013; Benkler & Nissenbaum, 2006; Benkler, Shaw, & Hill, 2013).

Right to the city: Citizen responses to the crisis

Among the world-wide spate of citizen-led movements responding to the diminishing of political engagement and participation opportunities brought by the so-called urban crisis, the Right to the City has called the attention of critical urban theorists as it challenges the status quo in city governance (Corsín Jiménez & Estalella, 2013). By unpacking the concept of Right to the City and understanding its appropriations in activist movements in different localities, one can examine how citizens challenge contemporary manifestations of the urban crisis, shifting their role from docile residents to engaged co-creators of the city.

The concept of Right to the City implies four principles (Purcell, 2002). First, the concept redefines the city, towards a scenario for social and political encounters (Schmid, 2012) and decentralisation of the expert knowledge encapsulated by city planners and developers (Arnold, Gibbs, & Wright, 2003; Irvin & Stansbury, 2004). Second, Right to the City refers to the principle of appropriation, which implies a broad opening of spatial use of the city, including infrastructure and services, as well as the restructuration of the neoliberal governmentality and the control the means for urban production (Purcell, 2003) Third, Right to the city means a new conception of the principle of citizen participation, implying a deep change in current forms of decision-making in cities and the practices of representative democracy. Therefore, Right to the City stands for a collective emphasis of citizenship in urban governance, which demarcates the principle of co-production, advocating for diversity and the ‘wealthy knowledges’ (Foth et al., 2015) that multiculturalism bring together in the city.

Activist movements embracing the Right to the city in their agendas redefine, appropriate, participate, co-produce, and ultimately imagine the city. However, such perspective is far from being dominant in the urban governance arena. In the context of urban crises, then, becomes imperative to explore how such efforts engage, envision and crafts legitimate narratives (Foth, Odendaal, & Hearn, 2007) of their local struggles for obtaining more decisive leverage in urban governance and decision-making.

Imagining a citizen-led urbanism: City-production in future tense

Urban imaginaries, in the shape of oral stories, storytelling, poetry (Odendaal, 2006) and shared experiences, constitute a still unperceived, but enormously powerful material to be used in strategic community engagement and urban planning (Collie, 2011). As mechanisms to co-produce versions of the city based on citizen experiences, points of view and envisions of the future, urban imaginaries are citizen strategies to co-produce the city as lived urban space (Westwood, 1997).

Cities are the ever-fluctuating product of an array of forces, including social, political, and imaginative ones, that operate both from the top down and the bottom-up. In this sense, cities are collective intentions and plans. For instance, the Right to the City alliance narrates how they were “born out of desire and need […] for urban justice. But it was also born out of the power of an idea of a new kind of urban politics that asserts that everyone […] has a right to the city, [and] a right to shape it, [and] design it” (“Right to the City,” n.d., sec. Mission). The city that these activists have in mind is, then, shaped by their imagination. Cinar & Bender argue that the correlation between the material dimension of the city and the imaginary is expressed by “interactions, negotiations, and contestations yielding several competing narratives and images of the city that seek to give it a particular presence and identity’’ (2007, p. xxi). Therefore, the city, as spatial phenomenon under constant process of redefinition, depends of the fluctuations of the collective imaginary, i.e., shared “individual perceptions and experiences of urban space” (Kelley, 2013, p. 184).

Although the concept of urban imaginaries has been explored as an alternative way to gain insights about urban cultures and their relation with city-planning (Silva, 2003, 2012), conservatives perspectives in the field of urban planning are still reluctant to consider the cost-benefit balance of participatory city-making mechanisms and the type of datasets they produce (Sandercock, 2000). For instance, Irvin & Stansbury argue that “citizen participation may be ineffective and wasteful compared to traditional, top-down decision making under certain conditions” (Irvin & Stansbury, 2004, p. 62).

The concept of urban imaginaries aligns with Odendaal’s claims that, in order to reframe the current practices in urban planning and urban governance, and enable citizens to actively take part in decision-making, planners and local authorities need a more thorough “understanding of local conditions and sensitivity to local knowledge […] The access to this information is not necessarily through reports and documents, but may have to be gained through oral stories, storytelling, and poetry, for example” (2006, p. 566). Consequently, the emergence and establishment of urban imaginaries as engine of city shaping and representation of the collective desire, reveals a complex imbalance of power among different urban stakeholders. Cultural geographers like Bailly (1993) and Schrank (2008) locate the problem of the production of urban imaginaries in the context of citizen political representation in relation with the symbolic relevance of places within the city. The practice of power in urban planning and governance, for example, illustrates how those who control the means of ideological production (e.g., government, private developers and media outlets), tend to impose not only particular forms of shaping the cityscape, but also, as argued by Wilson (1998), the narratives to socially legitimise them. In this paper, we propose understanding the concept of urban imaginaries as those verbal and visual narratives conveyed by Right to the City – Brisbane members to legitimise their cultural world-views and political practices.

Methodology

We are interested in the production of citizen imaginaries as narrative schemes to interpret the transformation of urban life into symbolic representations through using imagination (Cinar & Bender, 2007). As cities are collective productions (Lefebvre, 1991), citizen imaginaries are also a result of collectively generated visual and textual narratives that work as socio-spatial meaning generators (Silva, 2003; Westwood, 1997). To study how local activist organisations claiming their right to the city are co-producing specific imaginaries, and, therefore, engaging and participating in the process of shaping the city according to their needs and desires, we chose an ethnographic approach to examine this phenomenon. This decision, implies an understanding of ethnography not only as a research method or writing style, but also as a platform for knowledge production that enables “the understanding and representation of [human] experience; presenting and explaining the culture in which this experience is located, but acknowledging that experience is entrained in the flow of history” (O’Reilly, 2012, p. 3).

We build on the argument of Lopes de Souza (2009), as well as on Brenner, Marcuse and Mayer (2012), whose work criticise scholarly approaches to citizen involvement in city production as immensely broad, with an eurocentric focus, and often short in considering local nuances of power struggles in urban governance. This study considers an ethnographic approach for understanding specific citizen realities as result of the tension between global phenomena (e.g., globalisation and urban crisis) and its local manifestations (e.g., lack of civic engagement and political participation in decision-making in specific cities).

We use digital ethnographic principles (Pink et al., 2015) to frame our ethnographic approach, as the everyday practices of Right to the City – Brisbane occur both in physical and in digital domains. This means :

a. our research considers different forms of engaging with the digital and physical interactions that define the practice of Right to the City – Brisbane;

b. although our research explores digitally mediated interactions of this activist organisation in social media channels, it does not necessarily consider those interactions as the centre of our enquiry;

c. our study embraces openness as it considers a transparent interchange of knowledge between Right to the City – Brisbane and ourselves;

d. our study involves a reflexive practice, as it recognises our own position as knowledge producers within a specific context of research; and,

e. our ethnographic exploration relies on complementary data sources, including Facebook data scraping and a collection of printed media, in addition to traditional ethnographic methods including participant observations and semi-structured interviews, aligning in this way with the multi-sited ethnographic paradigm (Hannerz, 2003; Marcus, 1995).

As Right to the City – Brisbane exists and performs both in digital and physical domains, and the production of their specific imaginaries of co-creation of the city revealed diverse communication channels and organised activities, we decided to conduct a non-local ethnographic exploration (Feldman, 2011) to illustrate how this group of activists appropriate, challenge and redefine through their practice the role of citizens in producing the city.

Research Methods & Techniques

Ethnographic participant observations

Since Right to the City – Brisbane schedules weekly meetings to organise group activities, work agendas and interventions in public space, we engaged in regular participant observations conducted over a period of six months, starting in October 2016. The average attendance at these observed weekly meetings ranged between 6-25 individuals, with roughly equal presence of both male and female attendees. Observations, which took place in different locations around the inner-southwestern suburbs of West End and Annerley, served the purpose of blending in and understanding the cultural context in which Right to the City – Brisbane collectively imagines and co-produces the city. In specific, participant observations facilitated the identification of collective practices, routines and rituals, as well as remarkable social patterns and outstanding events within the group (Wolfinger, 2002). Field-notes were taken by hand during and right after weekly meetings, planning gatherings and interventions in public space organised by the activist group, and digitally converted. Although these observations enabled a systematic collection of descriptive field-notes (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011) and printed media (Hannerz, 2003) produced by the activist organisation, participant observations did not constitute the only, nor the most relevant method for data collection.

Interviews

During participant observations, we identified key members of Right to the City – Brisbane and approached them as potential interviewees, following a maximum variation sampling criteria—that is, considering their age, cultural background and the level of engagement within the activist organisation, their meetings, working sessions and other public events (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). We conducted 5 one-on-one semi-structured interviews with 2 male and 3 female members, ranging between 45-90 minutes in length. The interviews were conducted strategically towards the end of our fieldwork (March 2017). Interviews aimed to deepen research insights obtained from participant observations, and grasping different individual perceptions and experiences of group members regarding their involvement in Right to the City – Brisbane engagement practices, visioning mechanisms and peer-production strategies (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). We chose to conduct the interviews after 6 months of engaging in participant observations within Right to the City – Brisbane, as the rapport and trust between participants and ourselves proved solid, and we could create the most comfortable conditions to open up a conversation with participants, rather than operating a strict interviewing protocol. In this sense, we followed an ethnographic interviewing technique, directing the conversation with the activist group members towards an interchange of knowledge between pairs and exploring “purposefully the meanings [participants] place on events in their worlds” (Sherman Heyl, 2001, p. 369).

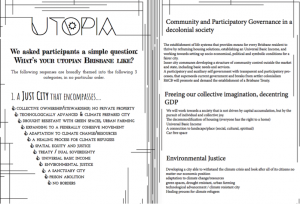

Printed media

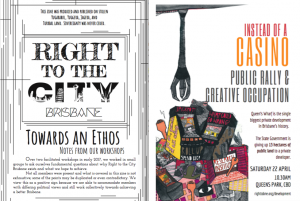

Right to the City – Brisbane produces a significant amount of printed media in the shape of posters, flyers and zines. The activist group uses this tangible media to produce and reproduce their vision on specific issues occurring in the city, as well as disseminating information about the political principles they stand for, and the activities and interventions they organise in public space (Figure 1). Since “Media, personal or impersonal, seem to leave their mark on most multi-site studies” (Hannerz, 2003, p. 212), we considered that collecting and exploring printed material may provide us an opportunity to explore both a unique perspective of this group’s experience on peer-producing the city, and the verbal and visual narrative forms used to convey such experience. This approach to printed media as a vehicle to explore citizen imaginaries through verbal and visual sources, has been explored by Silva (2003, 2012) in his attempt for decoding the production of urban cultures in Latin American capital cities. By including a printed media in our dataset, we align to a definition of ethnographic work as a matter of ‘polymorphous engagements,’ that is “collecting data eclectically in many different ways from a disparate array of sources, attending carefully to popular culture, and reading newspapers and official documents” (Gusterson, 1997).

Figure 1. Examples of posters, flyers and zines printed and distributed by Right to the City – Brisbane

Digital traces

Throughout our engagement and participation in the social and political dynamics of Right to the City – Brisbane, we examined the affordances, uses and limitations of digital outlets (Hine, 2000) such as the group Facebook public site (facebook.com/righttothecitybrisbane). Rather than centring our ethnographic enquiry in the use of social media to accelerate activist communication (Poell, 2014), or exploring how social media has transformed the activist group as a form of digital collective intelligence (Bastos & Mercea, 2015; Schuler, 2009), we took Right to the City – Brisbane Facebook site as an extension of our participant observation and as a space for searching traces of how this activist group engages with broader audiences, envisions the future city, and activates mechanisms of co-creating of their urban space. The collection of this digital traces implied a manual scraping of Right to the City public Facebook posts, in which not only the activist group spread information about local events, but also engaged in discussions with Facebook users from other affiliations – although discussions with other users occurred less often during the time we scraped Facebook data.

Data analysis

Due to the diverse nature of our dataset, we approached it by conducting a thematic analysis (Aronson, 1995). The coding of the data, directly related to the research questions that motivate this study, combined data pieces from all the described sources (i.e., participant observation field-notes, in-depth semi-structured interviews, printed media collection, and Facebook scraping), and were given equal weight as significant traces of the narrative peer production of activist imaginaries. Clustering our evidences into meaningful, although diverse, groups of data enabled us to outline a more complete image of the study settings. It also provided us the opportunity to establish connections across the events, discourses, actors perceptions and our own take of the studied phenomenon. Likewise, we argue that conducting a thematic analysis helped compare and create emerging analytical categories from early stages of our research endeavour, which served the purpose of identifying emergent categories, refine these early ones and create new and unexpected connections across the dataset.

Results and discussion

In the following, we present the major findings and discussions following our data analysis with the aim of revealing the specific forms in which Right to the City – Brisbane engages, plans and activates different participation mechanisms to contest local dominant power structures and governance practices in the city. This section presents and discusses, first, how Right to the City – Brisbane engages with Brisbane citizens. Second, we explore how Right to the City – Brisbane envisions the city. Finally, we examine how Righ to the City-Brisbane crafts the city.

How Right to the City – Brisbane engages with citizens?

Feeding on citizen frustrations

Right to the City – Brisbane publicly presents itself as a collective in which “we [can] exercise our rights to shape our city. From communal gardens to public housing – residents, not capital, shape our city” (“Right to the City – Brisbane – About,” n.d.). The group feeds from some Brisbane residents’ discontent and frustration caused by the perceived low impact of their decisions and opinions in the processes of urban planning and local governance. As pointed out by Osborne (2016), “A key driver of this new urban politics in Brisbane is an entrenched cynicism towards mainstream urban governance, which is seen as corruptible, profit-centric to the exclusion and harm of all other interests, and inhibiting our ability to attend to our responsibilities to the environment and to each other.” The group, then, stands as a unique activist scenario for citizen-led urbanism. The reflections and practices around citizen rights and agency in the process of decision-making in the city represent a major motivator for the group members to voluntarily joining in. One of the participants explained his motivations to join the group:

P1: There was a missing gap in Brisbane’s activist landscape. Of course there were people addressing environmental issues, and Unions defending workers rights. There were also [activist] organisations working around [urban] planning, [all of them] playing by the rules of the state power but not challenging it in terms of citizens rights and control over urban planning.

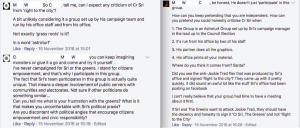

Right to the City – Brisbane is an activist grassroots organisation that presents itself as politically independent and citizen-oriented, although in its origins was tied to Australian Greens party representative Jonathan Sri’s successful campaign for a seat on the Brisbane City Council in March 2016 (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2016). The closeness and influence of Councillor Sri, although perceived as a potential risk in terms of the group independence – even with accusations of Right to the City – Brisbane to be an ‘astroturf’ group (Figure 2), is defended by its members as a positive feature, because it represents an innovative form of doing politics standing face to face with the electorate and including lay citizens in simple decision-making processes, such as local participatory budgeting (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Conversation between MW, a frequent Right to the City – Brisbane Facebook detractor, and C, member of the group. MW accuses the group of being an astroturf organisation, blindly favouring Councillor Sri’s political agenda.

Part of the discontent that drove many Right to the City – Brisbane members to get together under the movement pointed at insufficient democratic opportunities for citizens to engage, participate and decide about how to build the future city. The democratic reduction experienced by the group members, refers ultimately to a drastic concentration of decision-making power by city authorities, their incapability to redistribute such power in realistic ways, and the ‘tokenistic’ and opportunistic political practices that make the electorate feel manipulated. When asked about their impression on how Brisbane authorities performed in terms of governance practices, one participant commented:

P4: Brisbane City Council has a very thin veneer of democracy. Most decision-making is very hierarchical and centralised. In terms of consulting directly with citizens, [BCC councillors] are very tokenistic and shallow, and most important, [consultation] only appears around election times. That’s when you see [councillors] conduct consultation meetings, deploying surveys that are all predetermined.

Figure 3. A Facebook invitation for urban residents to engage in participatory budgeting workshops organised by Councillor Jonathan Sri.

Politics doesn’t have to be boring

Being playful and having fun and making friends describe three of the Right to the City – Brisbane engagement mechanisms. Through play, Right to the City – Brisbane members represent, criticise and challenge the values of current political practices. An example is illustrated by the staging of a satirical wedding between a corrupted politician and a greedy developer (Figures 4 & 5). The wedding was a playful way to denounce the alarming influence of private corporations in local development decisions. Using satire, Right to the City – Brisbane conducts a strong criticism of the current state of power relations in Brisbane governance without necessarily being obligated to point out any particular names or starting legal allegations against public servers. Choi (2010) argues that play is a ‘liminal’ activity situated between imagination and reality, and between the margins of social pressure and individual freedom. Given this, the group uses play as a powerful alternative to execute reciprocal, ethical control over the local authorities who hold the power of shaping Brisbane.

Embracing play as a form of contestation is not exclusive of Right to the City – Brisbane. Ministarstvo prostora (Ministry of space), https://www.facebook.com/MinistarstvoProstora/, a Serbian activist organisation that reacts to government’s lack of support for cultural activities, infrastructure and allocation of budget, by conducting appropriation actions across Belgrade and other cities, specially focused in creative occupation of spaces for artistic, cinematographic and urban exploration activities. Although the differences, mostly around the type of practices and the political demands, both movements illustrate how citizen-based organisations re-imagine the city by challenging taken-for-granted social orders.

Right to the City – Brisbane members are guided by ‘having fun’ as one of the most important outcomes of their engagement with the serious topic of local politics. When describing what makes Right to the City different to other activist groups in Brisbane, one participant referred to the happy group atmosphere as a determinant factor for new members to remain:

P3: When T and his boyfriend joined Right to the City – Brisbane, was because we co-organised one of the Free University sessions at the Bearded Lady, you know, that dancing bar in Boundary [Street]. When they saw that we were talking about serious shit in a non conventional site, when they saw that everyone could participate, and specially when they saw us having fun and laughing, they couldn’t resist and have been with us since then.

Figure 4. Satiric wedding between a corrupted politician and a greedy developer.

Having fun goes beyond being just a recruitment practice. As described by another participant, having fun involves a distinct way to understand social interactions as part of the social transformation that the city requires to become a place of encounters (Lefebvre, 1996). This explains why Right to the City – Brisbane conduct their activities and interventions around creating social atmospheres that inspire happiness and social interactions. As argued by one participant when asked by the nature of Break the Boundary, an impromptu carnival organised by the group which occupied Russell Street, West End, on September 2016:

P2: With a normal protest you have around hundred people united under one idea. That’s great, but nobody knows each other. We wanted [with Break the boundary] to create the conditions for people to encounter, to experience each other, to socialise.

Figure 5. Politics doesn’t have to be boring.

Camaraderie is also one of the defining mechanisms Right to the City – Brisbane employs for engagement. In our first encounter with the group, we registered in our field notes: “Sitting around a table on the ground level, there were a bunch of young people mostly in their late twenties. In a matter of 10 minutes after my arrival, the group got bigger in numbers (around 20 people in total). It captured my attention that there were only two people, a couple, in their fifties. Before the ‘serious’ conversation got started, people had time to talk. Most of the attendees ordered beer from the bar. I engaged in a couple of placid chit chats with strangers” (Field Note 29/09/2016). There are two elements to highlight in this note. First, Right to the City – Brisbane is an organisation that attracts and gets defined mostly by young people from a particular age-segment. Second, members encourage socialisation as a relaxed mechanism to start serious conversations about their political practice. These two characteristics revealed a unique feature of the group engagement practices, i.e., using friendship as a cohesive and meaningful form of structuring the organisation. By relying on friendship, the group not also increases local solidarities – what has been described by (Landau, 2017) in the context of African cities as ‘communities of convenience’. As a community of friends, Right to the City – Brisbane materialise and increase effective functional relationships within the group members and the community in which they act upon (Bunnell, Yea, Peake, Skelton, & Smith, 2011). One participant commented:

P1: I’m aware that groups like RttC are highly relational. There are no designated conflict resolution officers, and there are no formal complaint mechanisms. So we rely pretty much on our capability of mediating conflict and disagreements by getting people talking about it.

(Un)structured hierarchies: the nature of internal organisation

We registered these words in our field notes: “When I got there, I saw how nearly everyone putting their belongings on the side and rushing up to collect chairs and set up the room. Nobody suggested how to locate the chairs, but in an ‘instinctive’ way, we all organise the chairs forming a big circle” (29/09/2016). Later on, we annotated how “The meeting started with an established ritual. We sat in a circle and provided a brief update on who we were and how we felt. I have undervalued this greeting practice, but I started noticing how important and welcoming it is, particularly for those who turn up for the first time” (20/10/2016). Sitting in a circle (Figure 6), is the first indication of how Right to the City – Brisbane members contest hierarchical organisation structures. However, the group praises and nurtures the generation of new leaders among the group members.

Although it seems paradoxical, the anti-hierarchical organisation form does not contrast with the formation of internal leadership, as pointed out by one of the participants:

P5: It is foolish to think Right to the City – Brisbane as a completely anti-hierarchical group just because there are no elected positions. Inherently, people who can spend more time in organising and having their voices heard will acquire more power.

Those who have more time and put more effort end up calling the shots. How do you, then, control the accumulation of decision-making power within the group in the hands of those who participate the most? Another participants recognised that:

P3: The challenge [for Right to the City – Brisbane] is how to create mechanisms to decentralise power. A strategy that seems to work relatively well is to rotate roles. Facilitators, for instance, can set up agendas, sort out contents and shape conversations. They end up having some power. That’s why it’s important to share those roles around and give all people the skills and practice of facilitating. Another strategy [that Right to the City – Brisbane have tried] is having good feedback mechanisms where people feel happy with the decision being made.

Figure 6. Sitting in a circle as a ritualised expression of equality and power distribution.

Certainly, we noticed the formation of new leaders in the group during the time we observed participants. Likewise, we witnessed how those new leaders happened to be members with a major level of commitment. However, subtle management of decision-making power in hands of the leaders was not perceived by others as a menace to the power distribution among the members, but as natural consequence. In addition, not for being an expected effect, leadership was considered tantamount of tyrannism. Instead, rotating leadership is desired as a skill to be learnt, and as it can ‘get things done.’ In this regard, one participant claims that:

P4: Honestly, without [leaders] we all will be wasting hours of discussion. We do things here. We want things, and we do them. We value our capability of doing a lot of stuff and not only talking about it.

Right to the City – Brisbane put in practice simple but effective mechanisms for decision-making. In addition to incentivise leadership rotation, the group actively cares about the resources needed by the members when making informed decisions. The priority of the organisation relies in offering opportunities for members to upskill their knowledge, critic capacity and level of exposure with the surrounding community’s issues. The consolidation of effective networks and partnerships with other activist organisation, including Brisbane Free University, https://brisbanefreeuniversity.org/, a fellow movement standing for challenging the divide between the academy and the public in Brisbane, is considered a mechanism to build more accurate and effective argumentation capabilities to the group members. By participating in Brisbane Free University sessions, Right to the City – Brisbane members not only acquire argumentation skills, but also are recognised and valued as organic intellectuals (Forgacs, 1988), in possession of tacit, intuitive and local knowledge, highly needed to reframe the practices of urban governance (Sandercock & Lyssiotis, 2003). In terms of leveraging citizens agency in local decision-making and political participation, Right to the City – Brisbane conducts a series of hands-on mechanisms, including participatory budgeting sessions (Figure 7) and creative workshops (Figure 8). Again, these activities are intended not only for upskilling but also to communicate and put in practice empowering mechanisms to reimagine Brisbane as owned by its citizens.

Figure 7. Facebook invitation to a participatory budgeting session.

The loose internal organisation of Right to the City – Brisbane seems to overwrite what Bennett (2003) predicted in terms of digital activism. The group, which prefers to engage and interact through face to face practices, shows low vulnerability levels to control failures in decision-making situations. However, their scarce digital engagement have represented a slow growth of their political alliances and partnerships, contrary to the tendency on networked activist groups around the world (Juris, 2005). The success of Right to the City – Brisbane unstructured internal organisation depends on the relevance of their social ties, which at the time relies on the creation of conditions for camaraderie and the premise of playfulness and happiness. Only in this way, the group can engage effectively with their members. Right to the City – Brisbane members know they are achieving their goals by contrasting what they do with the feeling of the majority. They embrace a particular vision of the world and any proposed and developed activity is unspokenly contrasted against such vision. Right to the City – Brisbane does not have a formal, rigid and centralised code of conduct, system of values or written constitution. Instead, a social sanction system acts ‘instinctively’ if ideas or decisions tend to go against their shared values.

Figure 8. Community engagement through creative artworks as a mechanism to reimagine the city.

Right to the City – Brisbane engagement practices, then, echo “countercultural movements of the past — the Beats of the 1940s, Hippies of the 1960s, and Punks of the 1980s — all of whom critiqued capitalism and social climates of oppression” (2013, p. 58). As an example of an alternative movement, the group engages in political practices that challenge and reveal exclusionary patterns in current local government behaviour, fitting this way with Jeppesen’s (2012) definition of anarchist principles and values, i.e., “a critique of relations of domination, so anarchist values and practices are against domination, be it in the form of hierarchies, unequal power relations, structural inequities, or authoritarian behaviours” (2012, p. 264).

Audience outreaching and civic disobedience: the nature of external engagement

Right to the City – Brisbane recognises a major challenge in terms of their mechanisms for expanding their community base. Despite every event, meeting, and even every zine published by the group acknowledge and remember we are on ‘stolen land,’ the engagement, participation and scope of the group shows a low number of members who self-identify as traditional owners. Equally, involvement of diverse cultural background populations is not as high as expected, particularly when the group concentrate almost all their actions in West End, a socio-culturally and ethnically diverse area. After a conversation with one member of the group, we registered this in a field note: “the organisation struggles in diversifying and expanding its community base. ‘C’ claimed that in lesser interesting events, such as participatory budgeting, there were only 5 mid-aged, financially stable, white Australians attending to such working session” (20/09/2016). This situation raises a concern in terms of political representation and legitimacy, as it is unclear whose values does the group stand for, and more critically, under what criteria they claim the right to represent their community. Despite the group members’ discursive orientation towards acknowledging and vindicating the rights of historically oppressed over the territory and self-governance, levels of participation of traditional land owners was scarce. Beyond sporadic approaches with indigenous organisations and single individuals, meetings and other practices organised and executed by Right to the City – Brisbane proved insufficient to recognise the value, incorporate the visions and actively shape the city according to this particular population needs and desires (Porter, 2006). We will explore this discussion in section 4.3, as it relates to the group mechanisms to challenge current representational democratic values and practices.

One of the strategies followed by Right to the City – Brisbane for expanding their base and outreach wider audiences, is to engage in civic disobedience practices. As pointed out by one participant,

P2: If government decides that, for instance, young people don’t wanna [sic] get involved in any consultation just because they wouldn’t attend a meeting, Right to the City – Brisbane will continue to organise big public events [1] to demonstrate how young people actually do care about this, that young people mobilise with the right array of tools and mechanisms. We will also be appealing to do direct actions and encouraging pacific civic disobedience that directly makes demands to the government. Disruptive actions are useful to set up a guiding north, as our dreams are so far from the current ways in which the city is made that we can alert everyone that there is an alternative even though is not necessarily plausible right now.

Using disruptive actions in public spaces redirects the discussion in two different considerations. First, civic disobedience actions are, most of the time, the group modus operandi. The formula is well-practiced by media outlets, e.g., rating in TV shows or likes in Facebook. The more you appear notorious, the wider the audience you may speak to. Right to the City – Brisbane has exploited this principle for connecting with other population segments that may agree with the group ideological standings and practices. One participant commented:

P2: About the strategies we have put in place, I think we have done a good job in terms of remaining open and accessible to newcomers, so new people can come along and quickly get involved and participate in shaping key strategies and decisions. Second, civic disobedience practices relate directly with one of the funding principles of Right to the City as a political concept, i.e., city appropriation.

This means that Right to the City promulgates the right of urbanites to make use of the city, access its facilities and services, and occupy its existing spaces currently privileging a few urban actors (Osborne, 2016). The group’s principle of appropriation highlights that urban space is socially produced (Lefebvre, 1991, 1996), but the unbalanced power socio-spatial struggles framed under the umbrella of neoliberal policies in urban governance, often enable a reduced segment of city populations to execute their own and exclusionary right to the city. In Marcuse’s words: “Some already have the right to the city, are running it right now, have it well in hand. They are the financial powers, the real estate owners and speculators, the key political hierarchy of state power, the owners of the media” (2012, p. 32). By appropriation, Right to the City – Brisbane implies a restructuration of the neoliberal governmentality (Foucault, 1991), in other words, the rationality and the mechanisms of power in Brisbane governance, which exclude and disenfranchise populations in the city. Lastly, the principle of appropriation also refers to the capacity of controlling the mediums for producing a city that meets the needs and dreams of its residents (Purcell, 2003).

How Right to the City – Brisbane envisions the city?

A fair city

In Right to the City – Brisbane narratives, the city is envisioned as a fair one. The principle of social justice is the first and guiding reference to build up the city to the future. By envisioning a fair Brisbane, Right to the City – Brisbane members state a desired reality, and hence, a reality that mismatch the current conditions. As one participant stated:

P2: I would love to live in a city in which I could have the right to be myself without being judged. I would like a city that respects my views and specially a city that never commands me or tells me what to do.

As part of the fair city imaginary, group members dream of a Brisbane that provides equal economic, environmental, spatial liberties, contrasting with the inequalities derived from the implementation of neoliberal agendas in urban governance – i.e., governance-beyond-the-state (Swyngedouw, 2005). Similarly, a notion of a fair Brisbane reveals a desire of challenging capitalism as the structural source of disparities. The group members desire, for instance a reconsideration of private property, the establishment of a Brisbane Treaty, and the implementation of a Universal Basic Income (Figure 9). In this sense, the imagined fair Brisbane encompasses the definition of a city that solves the historical disadvantages of certain vulnerable populations, vindicating this way those who have been marginalised from basic schemes of representation. Right to the City – Brisbane, therefore, proposes a city that no longer comprises spaces for exclusion of any kind, but places for celebrating cultural, ethical and system-values difference as the formula for cohesion (Schmid, 2012).

Figure 9. A zine condensing group members ideas about Brisbane envisioned as a just city.

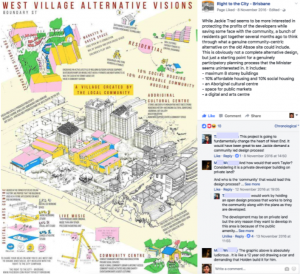

A sustainable city

Right to the City – Brisbane members envision a sustainable Brisbane. The definition of sustainability, although, is more comprehensive that its environmental or economic meanings. In our field notes we recorded that “the mention of the concept of sustainability during the meetings has gradually increased and transformed with the days. At first I thought it was a sort of conceptual bias, since there are many supporters of The Greens party. I guess I overlooked this concept and how dynamically it is used by the group. It seems they use it to refer to a sort of ecosystemic balance” (02/02/2017). Figure 10 illustrates how Right to the City – Brisbane members carefully addressed an alternative vision of the West Village development project, integrating not only people who may be ideally benefited by the construction project – e.g., Aboriginal residents, low income workers, and less privileged residents, but also representative institutions and elements of the cultural life of the community – e.g., community centres, art and music venues. Such holistic attention to the relations between actors and groups, has been used to describe the communicative ecology that guides the interactions of different actors involved in the food industry in Australia (Hearn, Collie, Lyle, Choi, & Foth, 2014). The implications for the case of Right to the City – Brisbane are related to the capability of their members to include a more comprehensive set of human and institutional actors within the spectrum of stakeholders involved in effective envisioning and planning, contesting how developers and city authorities conduct their profit-oriented development projects.

Far from being a feasible blueprint, the relevance of this vision of Brisbane as a sustainable city is the implied demand for residents to play a more informed and decisive role in planning their lived space. By designing an alternative view of the West Village development project, Right to the City – Brisbane members acted not as residents who were passively delegating responsibilities to city authorities, but as engaged city co-producers who were able to step up the participation ladder (Arnstein, 1969) catching a glimpse of citizen control.

Figure 10. Alternative proposal for West Village development project.

A decentralised city

Brisbane is desired as a decentralised city. Similarly to the sustainable city described above, the decentralised Brisbane refers to a comprehensive meaning of the concept. As explained by one participant,

P5: I foresee a sustainable, more decentralised city, not just in decision-making but also in terms of physical development. Rather that a city with wild densification, I’d like to see a shift towards urban villages and development nodes. So reclaiming that idea of walkable neighbourhood where people can live and work and encounter with others and create community. For me an utopian city refers to more small businesses and food coops rather than a few large corporations.

A redistribution of decision-making power that may enable a change in how citizens shape their urban space, is critical to consolidate the Right to the City – Brisbane project. However, a part of the decentralisation of decision-making and how it applies to the physicality of the city, the group member also pursue decentring capitalism as the framework in which commodification and gentrification of urban space is defined, naturalised, and taken for granted.

How Right to the City – Brisbane crafts the city?

Legitimising citizen experience as organic knowledge

Our data suggests that Right to the City – Brisbane challenges and attempts to redefine conventional and dominant assumptions of representative democracy. The group takes literally the Lefebvrian premise that the right to the city may be universally claimed by any city resident, no matter their affiliation to any ‘liberal democracies’ forms of citizenship (Purcell, 2002). Thus, as argued by Lefebvre (1996), the right to the city “is conferred by inhabitance — which is not a fixed or singular identity, but one that may reflect intersectionality and multiplicity” (Osborne, 2016). Undoubtedly, legitimating urban residents experience as an acceptable form of knowledge that may grant them the right to shape the cities, is a complex statement to assimilate. In our field notes we recorded our hesitation: “I threw up a question about how representative were [the activities Right to the City – Brisbane got engaged] in terms of matching community needs and desires. I was interested in starting to interrogate the ways in which they reckon, they listen, prioritise, model and represent their local communities expectations. My intervention generated a bit of disruption in the harmonic atmosphere. Interestingly, the man sitting next to me, just after he offered me fries, ordered by M minutes before, clarified to me that Right to the City – Brisbane effectively is an open initiative born from the community itself, and for that reason they all felt they represent the community needs and desires. Although they never mentioned any formal consultation mechanism for guaranteeing a transparent representation, they argued that appropriating or activating that ‘right to the city’ is beneficial for the entire community in a broad sense as they are leading by example and showing that we all have the power in our hands to make the city to our fit” (29/09/2016).

In their aim of legitimising urban residents’ experience as a major – and certainly overlooked – asset for the process of city co-production (Sandercock, 2000; Sandercock & Lyssiotis, 2003), Right to the City – Brisbane resembles Gramsci’s definition of organic intellectuals (Forgacs, 1988), since the activists articulate and represent citizens’ political desires and needs. An example to illustrate how Right to the City – Brisbane vindicates citizen experience as a major asset for city-coproduction is annotated in our field notes: “The group gets enthusiastic when any [meeting] participant points out how inept city authorities are. ‘M’, for instance, just claimed that by participating [in the participatory budgeting sessions] we all show [city authorities] that we know what’s best for our suburb” (22/09/2016). Hemphill and Leskowitz (2013) label as DIY activism the type of political practices that describe Right to the City – Brisbane approach and interventions as “their everyday practice of crafting radical alternatives to mainstream models of governance, consumption, and learning. DIY activists [like Right to the City – Brisbane] offer a revealing portrait of an evolving community of practice and radical new forms of knowledge sharing” (2013, p. 58).

One of the operative premises of the group is to consider themselves and other fellow urbanites as ‘citizen-planners’ (Friedmann, 2011). However, the fact that indigenous organisations and individuals (as much as other populations associated with any level of vulnerability, including ethnically diverse demographics and people with learning difficulties) rises concern about what type of city, and ‘whose rights’ (Marcuse, 2012) the group are vindicating. This finding was unexpected, since the political tone of the group discourse is based on social justice and equality, and suggests that there is a need for the organisation to embrace alternative forms of connecting with broader audiences and assimilate their imaginaries towards a more plural city. Right to the City – Brisbane is a tender, and sometimes limited, initiative to reframe current ways of citizen engagement in decision-making, which does not mean that their efforts are futile. In fact, as a already identified shortcoming by its members (see ‘Audience outreaching and civic disobedience: the nature of external engagement’ as part of section 4.1 in page 19), the organisation employs mechanism for upskilling their knowledge, reframe their engagement and outreaching practices, and extending their network of partner organisation in the local ecosystem.

Leading by example

In addition to legitimating city residents as rightful urban reshapers, Right to the City – Brisbane promotes a hands-on strategy to craft the city. Leading by example “overwrites the necessity of imposing any sort of moral, social or ethical sanctions proper of hierarchical organisations. Simultaneously, [the group] saves significant amount of efforts and resources by employing [leading by example] technique as they subtly privilege one way to do things, and expect everyone else to copy and incorporate the expected behaviour, no matter if it is about sitting in circles, mocking the Liberals [party members] or even establishing friendly and respectful conversation with the others” (13/10/2016). In the words of one participant:

P1: the way we run our meetings, that type of example to say, hey look this is another way to make community decisions. I guess practicing these decision-making processes internally is how we convey the processes we’d like to see in the society. Also, what we are doing here [at Right to the City – Brisbane] when we organise those big events and public forums is to show BCC that there is appetite for opening discussion about citizen engagement and participation in decision-making, because there is still a dominant belief within our political representatives that residents don’t wanna be consulted, that people don’t have time to discuss anything and that’s why they have elected representatives.

With a combination of playfulness, humour and pride for the local emblematic natural features that define Brisbane as a locality, the activist group decided to adopt a nickname that expresses a series of values aligned with their hands-on crafting approach to city production: They identify as “Wagun of Right to the City – Brisbane” (Figure 11), the Yugara name for brush turkeys. The selection of this nickname provokes, at least, two comments. First, the imperative need of adopting an aboriginal name for the group — even when the great majority of the group members are from different cultural backgrounds — as a sign of respect and justice for the traditional owners of this land. The decision of adopting an aboriginal name like ‘Wagun’ was the result of a process of consultation with the local aboriginal authorities, guardians of the territory in which the activist organisation develop almost all their activities. Adopting an aboriginal name carries out political implications for the group. By presenting themselves with an aboriginal name, Right to the City-Brisbane reveal their political posture, aligned with the vindication of exploited minorities and disenfranchised populations. Second, the selection of turkeys as the emblematic representation of resourcefulness and the ability of living on others’ waste, which evokes an interest for austerity and disconnection of the capitalist regime.

Figure 11. Brush Turkey or Wagun in Yugara language is the group’s emblematic animal.

The fact that they have chosen a brush turkey as the group emblematic animal connects with the strategy Right to the City – Brisbane uses for quick interventions and appropriations of urban space. Tactical urbanism interventions — e.g., unauthorised landscaping, rubbish collection ‘working bees’ in empty lots or building urban furniture after recyclable materials — refer to the right to the city principle of appropriation, which as it turns highlights that urban space is produced by unbalanced power socio-spatial struggles framed under the umbrella of neoliberal policies (Schmid, 2012), but also susceptible of being claimed back by those in dispossession of such right. Likewise, such interventions convey the message that activism goes beyond protesting by embodying the active and transformative principle of action (“Rethink Activism,” n.d.)

Digital resistance, zines and mediums ownership

Right to the City – Brisbane follows an unstructured strategy to disseminate information regarding their principles and action plans, as well as to engage in political debates with stakeholders and other communication-related activities. As specified before, the activist group takes advantage of “the wealth of knowledge, wisdom, and experiences collectively and privately held by each urbanite” (Foth et al., 2015, p. vi) such as the group members, and translate it into their avenues to connect with the general public. The group makes use of its members skills and capabilities. For instance, local artists like ‘Mama.see,’ who is a member of the collective, creates most of the artwork published in zines and pamphlets and a Facebook site (facebook.com/righttothecitybrisbane). Printed anarchist media (Jeppesen, 2012) appears as a resource for ideological reaffirmation widely accepted by the members of Right to the City – Brisbane. The content portrayed in zines and pamphlets produced by the group (Figure 12) reinforces contracultural values – e.g., anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist, pro-equality, pro-minorities – and convey an imaginary in which the city is considered a ground for “direct democracy, participation, cooperation, collective self-determination, taking action to create change, mutual respect, long-term accountability, and lived social equality, among others” (Jeppesen, 2012, p. 265). In addition, the production of zines as part of the signature communication strategies of Right to the City – Brisbane members also relates to the idea of hand-made crafting. Zines contents are designed as original pieces and provide glimpses of the narratives used by the group to configure their own political identity and political agenda. In them, the activist group members explore, create and communicate “chaotic, disturbing, uncomfortable, sensual, complex, loud, confronting, humorous, and often a pointed and acerbic critique of mainstream culture and contemporary life,” labeled by Chidgey as DIY media (2014, p. 101).

Right to the City – Brisbane also communicates through a Facebook site. However, using digital platforms reveals an important variant with respect to the use of DIY anarchist printed media. One participant described her thoughts about Right to the City – Brisbane Facebook site as:

P2: [Facebook interactions] are necessary. It’s a necessary pain. I get that. You can spread info wider and quicker. I feel we only use it for that reason. But, honestly, I feel we are different because I don’t like the whole day looking at the screen. I rather talk with you and invite you to a beer or something. I think we do more when we can see each other.

The group members understand social media channels from a utilitarian angle. The Facebook site, for instance, provides just a means for getting in contact with a wider audience, a scheduling assistant for the group meeting and interventions, and a tool for attracting new members. Although digital platforms like Facebook are seen by the group as useful, a sense of distrust and resistance to them becomes evident. The ‘necessary pain’ of using Facebook is only justified as the platform appears as a dominant scenario for networking well-spread throughout the world, but, as noted by the same participant, the digital platform is perceived as limited, suspicious and alien to the imaginary of city that the group desires:

P2: [Facebook] helps with the invitations to our events. But, you know? You call me paranoid or whatever, but Facebook is just about selling you stuff. It’s not just a simple [scheduling] tool. I think it’s evil. I think also that there’s a hidden agenda that serves equally evil purposes. I don’t like it, but I guess we kind of need it.

Figure 12. Example of a printed anarchist zine used as a campaigning tool by Right to the City – Brisbane.

The resistance to embrace digital platforms like Facebook relates to numerous factors. First, Right to the City – Brisbane members perceive Facebook as a dually powerful tool, which enable both visibility and invisibility of certain populations and socio-political practices. This dual property has been highlighted by Shaw and Graham in their examination of Google, as “it is by virtue of this control [over digital information] that Google has the power to control the reproduction of urban space” (2017, p. 4). Facebook generates scepticism as it is perceived by the group as a space for the reproduction of exclusionary practices (Leszczynski, 2014) and reproduction of neoliberal and tokenistic political schemes and agendas in local governance (Greenfield, 2013; Žižek, 2009). By interpreting social media platforms as manipulated (and manipulating) devices, Right to the City – Brisbane members are not only diminishing the instrumental potential for broader outreaching. They are also missing out further opportunities for enriching their principles, practices and mechanisms by establishing nurturing and strategic networks with potential partners in local and global levels (Aiello, Tarantino, & Oakley, 2017).

In addition, the group reluctance to fully embrace Facebook or any other digital media platform relates, according to our view, to their misinterpretation of the sense of ownership as “a form of engagement, responsibility and stewardship” (De Lange & de Waal, 2013). Let us unpack this idea. Firstly, we found that Right to the City – Brisbane have focused their engagement strategies in social, face-to-face interactions, dismissing the mediated forms and the novel opportunities to “participate in important decisions, such as urban policies and design” (Antoniadis & Apostol, 2014). Interestingly, we observed that key members of the collective like BCC councillor Jonathan Sri were considerably active in Facebook, using the platform as a space for political engagement and decision-making in matter regarding his electorate. Unfortunately, our observations did not provide enough empirical evidence to articulate a discussion about the reasons for such dissonant practice between the group and single members. Secondly, and still following De Lange and de Waal (2013), we noticed a sense of obliviousness in how the group understands the capacity of digital technologies for leveraging and help crafting novel frameworks of civic co-responsibility (Dean, 2001). The attitude Right to the City – Brisbane manifest towards digital engagements ended up conditioning their capacity of automating and democratising their avenues for identifying civic issues, sharing their concerns and perspectives with key potential partners, and assuming agency for taking action. Lastly, we observe the activist collective misinterpreted the role of digital technologies for gaining control over public institutions, which already have done efforts for implementing e-based inclusive strategies, like the case of Government 2.0 Taskforce, http://gov2.net.au/, in Australia (Hui & Hayllar, 2010).

In this context, Right to the City – Brisbane refreshes the categorisations of contemporary social movements focused on networked and digital activism (Juris, 2005; Postill, 2014), decentralised real-time coordinating groups (Rekow, 2015), and online non-participation movements (Andersson, 2016) by practicing a resistance of media, instead of a resistance on media (Fenton, 2008). This implies that Right to the City – Brisbane uses consciously and carefully new (old) mechanisms for resisting and re-imagining the local city governance scenario.

Conclusions

“We change ourselves by changing our world and vice versa.

This dialectical relation lies at the root of all human labour.

Imagination and desire play their part.” (Harvey, 2003b)

This study has explored the engagement practices, the envisioned narratives and the crafting mechanisms put in place by Right to the City – Brisbane, an activist organisation that challenges conventional practices of local governance by encouraging a shift in the role of citizens as city co-producers and peer producing alternative imaginaries of the city. In particular, we have examined how Right to the City – Brisbane addresses Harvey’s questions for the uniqueness of activist movements in terms of unpacking “what kind of city […] what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values [the activist group] desire” (“David Harvey: The Right to the City,” September-October 2008, p. 1).

We have shown how Right to the City – Brisbane deals with a global issue including the shrinking of democratic opportunities for urban residents to realistically engage and participate in civic matters materialised in the consultation meetings and surveys, perceived by the group organisation as ‘highly centralises, predetermined and shallow’ (see participant 4’s comment in ‘Feeding on citizen frustrations’ in section 4.1). The activist organisation responds to the local context – nuanced by the high influence of private developers in the decision-making arena – by gathering the principles of Lefebvre’s (1996) concept and capitalising it as a form to recruit already politically frustrated citizens. To engage with the local reality, with other urban residents, and with the political praxis, Right to the City – Brisbane embraces playfulness and fun as active principles. Their decision to have fun while dealing with the serious business of challenging local governance, has attracted criticism from other residents who disagree with their mechanisms and political linkages, but, simultaneously, has resulted in a refreshing alternative for the local activist landscape in Brisbane, attracting a growing number of youngsters, often on the fringes of political engagement and participation. By actively promoting anti-hierarchical, anti-capitalist and citizen-led empowerment values and engaging in internal political practices of redistribution of decision-making power, Right to the City – Brisbane portrays itself as a DIY activist movement with a strong resemblance of contracultural anarchist organisations from past decades. This characterisation is, in addition, supported by the group’s engagement in public disobedience actions and alternative protesting.

Right to the City – Brisbane co-produces a series of narratives expressed both visually and verbally, in which they convey a particular form of understanding and projecting the city. Permeated by their members’ political worldview, Right to the City – Brisbane imagines a fair city where the principle of social justice stands as a beacon for inclusive participation practices. The Brisbane that this activist group construct imaginatively is also one where citizens can be assumed as part of a sustainable political ecology. The group also imagines a city that effectively redistributes power among its stakeholders, and that, by doing that, challenges forms of centralisation of resources, capital and infrastructure. These urban imaginaries are narrated as the blueprint of the type of city Right to the City – Brisbane activist would like to produce and live. Their imaginaries provide the guidance, in the shape of principles and values, for the future city. Furthermore, such imaginaries also inform the type of citizen the group members attempt to build: a one with the willingness, skills and agency to transform ideas into actions. The significance of unpacking Right to the City – Brisbane imaginaries relies on the provision of more meaningful insights for the process of local governance in cities. These urban imaginaries contain specific information that Odendaal (2006) suggests may not be captured by current top-down urban planning procedures.

Right to the City – Brisbane crafts such urban imaginaries by challenging taken-for-granted assumptions of representative democracy and its governance mechanisms. The group promotes citizen experience as a legitimate form of knowledge for shaping the city, moving close to direct democracy practices. As organic intellectuals, citizens should know what is better for the future of their inhabited spaces. This statement defies the verticality of governance models in which expert knowledge, embodied and practiced exclusionary by city authorities – and recently highly influenced by private developers under neoliberal governance paradigms. Right to the City – Brisbane members act out the city they imagine, performing as ethical role models for their fellow residents. As the city – and the citizenship also – implies an everyday construction, the group members define the type of city they may like to encounter and share with, by performing it and by lively showing to others how to make it their urban commons (Foth, 2017). Right to the City – Brisbane combines a city-crafting strategy that involves the production and reproduction of contracultural values materialised in printed media, and a thoughtful resistance to digital media, which gives the group a sense of uniqueness especially when compared to social movements focused on networked activism. The group and their city-crafting strategies reveal a distinctive form of peer-production based on a combination of digital and physical interactions. The engagement and participation practices of this local movement are informed by a collective expectation for a different city, and a different assumption of their role as co-producers. Practices included actively considering citizen experiences as valid knowledge for shaping the city, defining them as ‘citizens-planners’ (Friedmann, 2011). Also, engaging in co-creative occupation of spaces to resignify the public value of the city and challenge ongoing spatial commodification. These are examples illustrating how Right to the City – Brisbane co-produce the city, resembling Soja’s ‘thirdspace’ (1998), as for these activist, Brisbane is both an idea under construction and the hand-son take involve to materialise such plans. However, their reluctance to embrace the affordances of digital practices and tools for enabling themselves, and those who the organisation claim to represent, a deeper understanding of the urban realities they desire to transform, rises questions about the organisation insufficient literacy, commitment and scope. Despite the claims of digital platforms as reproducers of neoliberal inequities, they also encapsulate the potential for users to understand, challenge and own (De Lange & de Waal, 2013) the means for producing and shaping the city, both a physical and an imagined construction (Antoniadis & Apostol, 2014; Soja, 1998). By transforming their approach to digital technologies, the group may explore new scenarios for citizen empowerment (Barrett, 2013; Purcell, 2003). Cases such as the networked synchronisation practised by digitally engaged users in Rio de Janeiro’s streets during the years of 2014-2016 (Rekow, 2015), evidence the potential for citizens to actively challenge exclusionary practices in urban governance.

The unique forms in which Right to the City – Brisbane engages, envisions and crafts the city, all based in a hyperlocal interpretation of global issues related to inequality and citizen disenfranchising in city governance and production, resembles a Janus-faced duality. This activist organisation advocates for a progressive, contemporary, and digitally engaged approach to co-producing Brisbane, while at the same time it sources inspiration from values, practices and worldviews anchored in countercultural movements from past decades. Perhaps the dualistic nature of Right to the City– Brisbane may help other social movements around the world to reflect about their outreaching and engagement-related issues, and consequently, to reframe their mechanisms to imagine a new city tailored according to their needs and dreams.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our great admiration and gratitude to the Right to the City – Brisbane group. Their openness, commitment and disinterested contributions to this study are highly appreciated.

End Notes

References

Aarsæther, N., Nyseth, T., & Bjørnå, H. (2011). Two networks, one city: Democracy and governance networks in urban transformation. European Urban and Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411403988

Aiello, G., Tarantino, M., & Oakley, K. (2017). Communicating the City: Meanings, Practices, Interactions. Peter Lang. Retrieved from https://market.android.com/details?id=book-OiMZvgAACAAJ

Andersson, L. (2016). No Digital“ Castles in the Air”: Online Non-Participation and the Radical Left. Media and Communication.

Antoniadis, P., & Apostol, I. (2014). The Right (s) to the Hybrid City and the Role of DIY Networking. The Journal of Community Informatics, 10(3). Retrieved from http://www.ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/1092

Arnold, M., Gibbs, M. R., & Wright, P. (2003). Intranets and Local Community:“Yes, an intranet is all very well, but do we still get free beer and a barbeque?” In Communities and technologies (pp. 185–204). Springer.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Aronson, J. (1995). A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. The Qualitative Report, 2(1), 1–3.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2016, March 23). Greens win first Queensland local government seat. Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-03-23/greens-win-first-queensland-council-seat-gabba-sri/7270758

Bailly, A. S. (1993). Spatial imaginary and geography: A plea for the geography of representations. GeoJournal.

Barrett, D. (2013). DIY Democracy: The Direct Action Politics of U.S. Punk Collectives. American Studies , 52(2), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1353/ams.2013.0039

Bastos, M. T., & Mercea, D. (2015). Serial activists: Political Twitter beyond influentials and the twittertariat. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815584764

Belda-Miquel, S., Peris Blanes, J., & Frediani, A. (2016). Institutionalization and Depoliticization of the Right to the City: Changing Scenarios for Radical Social Movements. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(2), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12382